Na sessão das 18:15 de ontem, a sala IMAX esgotou. Gente jovem a entrar com pacotes de pipocas e Coca Cola, se avistei bem. Não conseguimos melhor do que dois lugares na última fila do canto esquerdo, quase debaixo de uma das colunas de som. O primeiro sinal acústico foi um estrondo que se prolongou com intermitências durante a apresentação de três ou quatro filmes surrealistas, certamente apreciadíssimos por espectadores mamadores de pipocas com sal ou com açúcar.

---

The world reckons with a new ‘Oppenheimer moment’

|

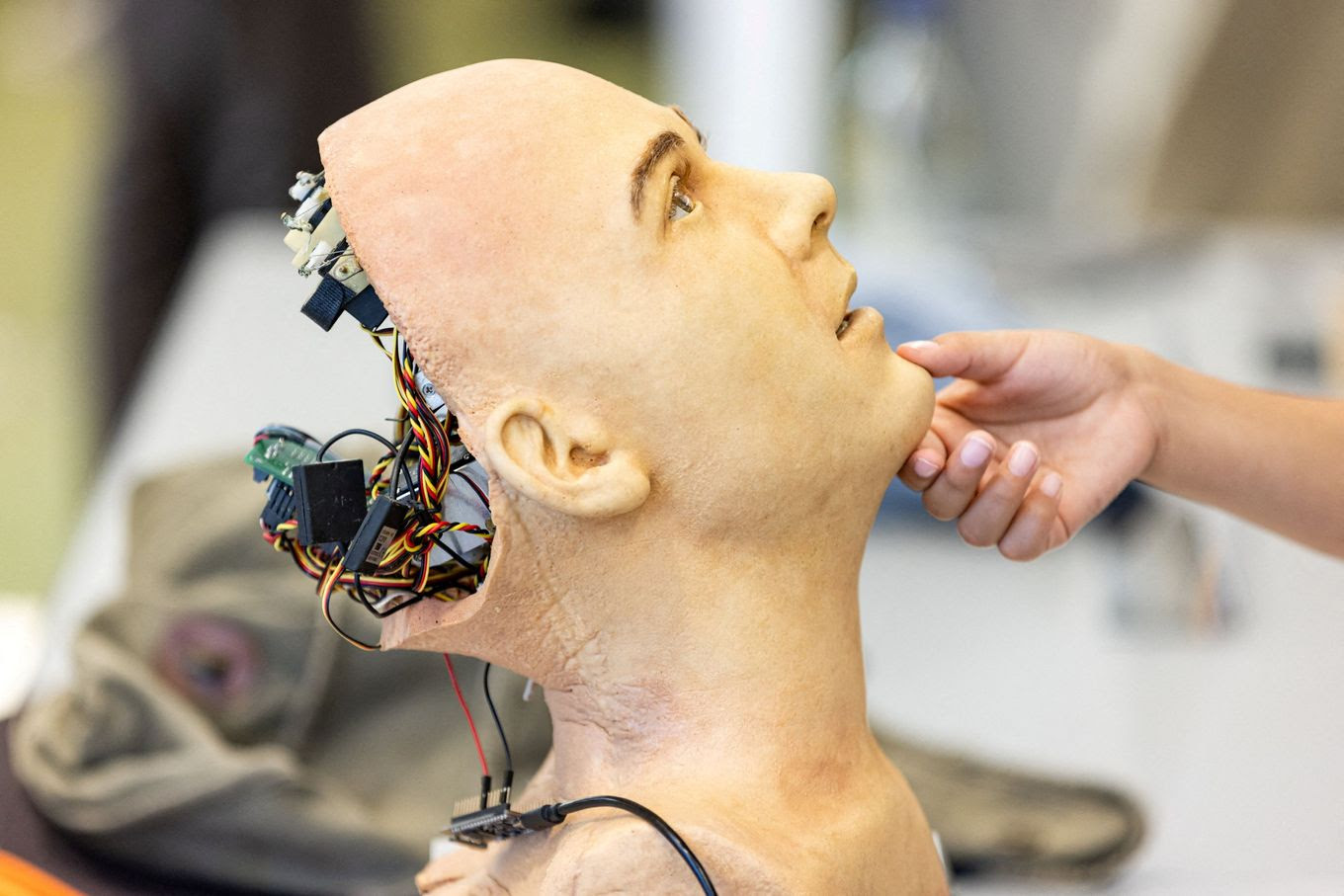

Advanced humanoid robot Sophia at the AI for Good Global Summit in Geneva on July 6. (Pierre Albouy/Reuters) |

No, Today’s WorldView has not had a chance to see “Oppenheimer” yet. The problem for Today’s WorldView is that he has a 21-month-old who is perfectly capable of devising her own cataclysmic schemes. But the profound cultural interest in Christopher Nolan’s biopic of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, is inescapable.

The titular character played by Cillian Murphy is a “part machinist, part mystic, ever questioning the apocalyptic implications of what he’s discovering,” my colleague Anne Hornaday wrote in her review of the film. Oppenheimer grappled with what he had wrought for the rest of his life. In 1945, after the bomb’s first test, he lamented that his invention wasn’t ready soon enough to wield against Nazi Germany — which he reviled as a Jew and long-standing anti-fascist. But later, after Oppenheimer saw its devastating use over two cities in Japan, a mission for which he aided in the preparation, he allegedly confided to President Harry S. Truman during their lone White House meeting that he felt he had “blood on his hands” and urged the president to reconsider amassing a stockpile of nuclear weapons.

|

||||

Such advice did not go down well with Truman, who — my colleague Timothy Bella writes — complained to his aides about the “crybaby scientist.” “He didn’t convince the president, and the president didn’t like him, unfortunately,” Charles Oppenheimer, the physicist’s grandson, told Bella. “My grandfather gave the right advice, and the president didn’t take it. What he said about having blood on his hands was clearly something Truman didn’t like.”

As it became clear that the Soviet Union was also building up its nuclear arsenal, faster than expected, Oppenheimer recognized the grim geostrategic stakes taking hold. “We may anticipate a state of affairs in which two Great Powers will each be in a position to put an end to the civilization and life of the other, though not without risking its own,” he wrote in a 1953 essay in Foreign Affairs. “We may be likened to two scorpions in a bottle, each capable of killing the other, but only at the risk of his own life.”

A year later, in large part due to his documented leftist sympathies before World War II, including close relationships with communists, Oppenheimer got swept up in the dragnet of anti-communist hysteria that consumed Washington at the time. The creator of America’s atomic bomb had his top-level security clearance revoked after the indignity of a four-week, closed-door hearing.

|

In Nolan’s view, Oppenheimer’s angst has a contemporary political and moral valence. As scientists and policymakers in the 1940s and ’50s were coming to terms with their harnessing of a power that could lead to a species-level extinction event for humanity, their successors face what could be a similarly fraught and mind-bending emergence of generative artificial intelligence.

|

||||

“When I talk to the leading researchers in the field of AI right now … they literally refer to this as their Oppenheimer moment,” Nolan told NBC News last week. “They’re looking to his story to say ‘OK, what are the responsibilities for scientists developing new technologies that may have unintended consequences?’”

In a guest essay for the New York Times published Tuesday, Alexander C. Karp, the CEO of Palantir, a big data analytics company that works with the Pentagon, writes: “We have now arrived at a similar crossroads in the science of computing, a crossroads that connects engineering and ethics, where we will again have to choose whether to proceed with the development of a technology whose power and potential we do not yet fully apprehend.”

The technological uses of machine learning systems are diverse and vast, but, as the introduction of OpenAI’s ChatGPT has already made clear, few corners of human society will be left untouched as AI tools evolve and grow more sophisticated and powerful. Whole industries and professions are likely to disappear — certainly, your humble newsletter scribe feels the spectral tug of obsolescence.

More gravely, this generation’s Oppenheimers by Nolan’s conceit, AI founders such as former Google executive Geoffrey Hinton and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, publicly acknowledge the genuine risks of an AI model going rogue, hijacking weapons systems or releasing pathogens or following some other terrifying algorithmic goal that would have apocalyptic consequences for humanity. They also express amazement and perhaps a degree of alarm at how swiftly AI systems are developing, already eclipsing human abilities in some significant ways.

In a New York Times interview earlier this year, Hinton, who is credited as being “AI’s godfather,” cast into doubt the value of his life’s work. “It is hard to see how you can prevent the bad actors from using it for bad things,” he said. In justifying his reasons for working on AI, he paraphrased Oppenheimer’s own explanation for why he chose to develop the atomic bomb: “When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it.”

The contours of the Cold War and the disturbing logic of “mutually assured destruction” became rather clear to all in the years after World War II. But we are still in the bewilderment stage of the age of generative AI. Governments are putting forward initial attempts at legislation placing checks on the technology’s usage — consider, a pioneering draft law that may be passed by the European Parliament later this year. Tech companies, while vowing a focus on ethics and human responsibility, are chafing against future regulation. And military strategists are already warning of an emerging AI arms race, with the United States and China racing ahead.

Last week, Lt. Gen. Richard G. Moore Jr., a three-star Air Force general, laid out the contest over AI in somewhat baffling ideological terms, suggesting the United States’ “Judeo-Christian” character would prevent its planners from misusing AI. “Regardless of what your beliefs are, our society is a Judeo-Christian society, and we have a moral compass. Not everybody does,” Moore said at a think-tank event in Washington. “And there are those that are willing to go for the ends regardless of what means have to be employed.”

Some U.S. lawmakers want more solid guarantees. Earlier this month, Sen. Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.) put forward legislation that would ban the use of AI in making nuclear launch decisions. He did so with the endorsement of Kai Bird, co-author of “American Prometheus,” a Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Oppenheimer on which the Nolan film is based.

“Humanity missed a crucial opportunity at the outset of the nuclear age to avoid a nuclear arms race that has since kept us on the brink of destruction for decades,” Bird said in a statement. “We face the prospect of a new danger: the increasing automation of warfare. We must forestall the AI arms race.”

No comments:

Post a Comment